What Is A Business Process

Business development and sales are two important aspects of the selling life cycle and while it can be easy to focus on one over the other neither should be neglected. This article will explain both aspects of the sales cycle and provide a clear.

What is a Business Process?

Most people intuitively understand a business process to be a procedure or event with the purpose of reaching a goal. When looking at our UML Airport we can find many different business processes and goals:

Definition of an “As Is” Business Process. An “as is” business process defines the current state of the business process in a organization. Typically the analysis goal in putting together the current state process is to clarify exactly how the business process works today, kinks and all. How to Analyze an “As Is” Business Process. Business process management (BPM) is a discipline in operations management in which people use various methods to discover, model, analyze, measure, improve, optimize, and automate business processes. BPM focuses on improving corporate performance by managing business processes. Any combination of methods used to manage a company's business processes is BPM.

- The goal of our passenger is to go on vacation. To achieve this goal, he has to book a flight and hotel, pack his bags, drive to the UML Airport, check in and board his airplane, exit the plane at his destination airport, go to the hotel, move into his room, and unpack his bags.

- The owner of the newsstand at the UML Airport wants to sell her goods. For this, she buys items inexpensively and sells them to her customers at a higher price.

- In order for passengers to check in at the UML Airport, an employee of passenger services accepts their tickets and luggage, inquires about their seat preferences, and uses an IT system. By the end of the procedure, the passengers receive their boarding passes on which their reserved seats and the appropriate gates are marked.

As you can see, business processes are often completed in several steps. These steps are also referred to as activities, and have to be completed in a predetermined order. The newsstand owner cannot sell any goods unless she has purchased them beforehand.

A passenger packs his or her suitcase before he or she drives to the airport. The employee of passenger services at the check-in counter can only issue a boarding pass after check-in is completed (Figure 3.1):

Activities can run sequentially or in parallel. Thus, a passenger can buy a bottle of whiskey in the duty-free shop, while his or her luggage is being loaded into the Airbus 320 to London.

Individual activities can be organizationally distributed. The check-in procedure takes place at the check-in counter and is performed by an employee of passenger services, while the subsequent boarding occurs at a different location and is performed by different employees of passenger services.

Usually, the activities of a business process are interdependent. This interdependency is created by the interaction of all the activities belonging to a business process that pursue one common goal.

Think about which of the following activities are not interdependent with our case study, because they do not pursue the goal of our passenger to go on vacation in an Airbus 320:

- Loading of the Airbus 320 with food and beverages

- Fueling of a Boeing 737

- Cleaning of the UML Airport restrooms

- Promotion of a UML Airport employee to vice-president

Definition of the Workflow Management Coalition

Official definitions of the terms process and business process were adopted by the Workflow Management Coalition. The following definitions can be found in the glossary of the Workflow Reference Model of the Workflow Management Coalition:

“A process is a coordinated (parallel and/or serial) set of process activity(s) that are connected in order to achieve a common goal. Such activities may consist of manual activity(s) and/or workflow activity(s).”

According to this definition, a process is a set of activities that occur in a coordinated manner, either in parallel or one after another, and that pursue one common goal. These activities can be performed manually or when supported by an IT system.

“A business process is a kind of process in the domain of business organizational structure and policy for the purpose of achieving business objectives.”

Business Systems

So far, we have explained business processes. Business processes are dynamic in nature and involve activities. However, if we want to look at the entire business system, we also have to consider the static aspects. This involves, for instance, the organizational structures within which business processes are conducted. This also involves various business objects and information objects, such as tickets or orders. For the static and dynamic aspects as a whole, we use the term business system.

In business terminology, a business system refers to the value-added chain, which describes the value-added process, meaning the supply of goods and services. A business can span one or several business systems.

Each business system, in itself, generates economic benefit. Thus, the business administrative meaning of business system does not differ very much from our use of the term business system. We also refer to the ‘results’ of a business system as ‘functionality’.

For the analysis and modeling of a business system it is important to define system limits. A business system that is to be modeled can span an entire organization. In this case, we talk about an organization model.

It is also possible to consider and model only a selected part of an organization. In our case study, an IT system is to be integrated into the Passenger Services operation. Therefore, it is sufficient to observe this operation and to narrow the business system to Passenger Services only.

Passenger Services is a division within the UML Airport, with employees, organizational structure, an IT system, and defined tasks (Figure 3.2). The surrounding divisions, such as baggage transportation or catering, also belong to the UML Airport, but not to our business system. So, we will treat them like other, external, business systems:

We are not interested in any of the external business systems as a whole, but only in the interfaces between them and our business system. For instance, the staff of passenger services need to know that they have to transfer passengers’ luggage to baggage transportation, so that it can be loaded into the airplane. Of course, for this, passenger services have to know how baggage transportation accepts luggage, so that it can be made available accordingly. It is possible that the IT systems of passenger services and baggage transportation will have to be connected, meaning that interfaces will have to be created. On the other hand, passenger services are completely unconcerned with how baggage transportation is organized, and whether each suitcase is individually carried across the runway or carts are used to transport luggage to the airplane.

Using UML to Model Business Processes and Business Systems

Before we move on to the modeling of business processes and business systems with UML, we should ask ourselves whether UML is even suitable for the modeling of business processes and business systems. For this purpose we will take a look at UML’s definition by OMG (Object Management Group Inc.—the international association that promotes open standards for object-oriented applications, which publishes each version of UML that is submitted for standardization at www.omg.org):

'The Unified Modeling Language is a visual language for specifying, constructing, and documenting the artifacts of systems'—UML Unified Modeling Language: Infrastructure, Version 2.0, Final Adopted Specifications, September 2003.

This definition indicates that UML is a language for the modeling and representation of systems in general, and thus, also of business systems.

In any case, UML fulfills at least one of the requirements of business-system modeling: it reflects various views of a business system, in order to capture its different aspects. The various standardized diagram types of UML meet this requirement, because every diagram gives a different view of the modeled business system.

We reach the limits of UML when modeling extensive business process projects, for instance, business process reengineering, or when modeling entire organizations. However, for these kinds of projects powerful methods and tools are available, such as Architecture of Integrated IT Systems (ARIS). This doesn’t mean that we want to keep anyone from using UML for projects like that, although we recommend a thorough study of the UML specifications (OMG: Unified Modeling Language: Superstructure, Version 2.0, Revised Final Adopted Specification, October 2004) and the use of CASE tools.

This text is tailored toward projects with the goal of developing IT systems. Moreover, it is tailored toward projects for which a concern of the business system is the assurance of the smooth integration of an IT system. The following characteristics mark such projects:

- Those business processes that are affected by the construction and integration of IT systems are considered.

- Business-process modeling is not the focus of these projects. Instead, the model serves as the foundation for the construction and integration of IT systems. Business process integration can determine the success or failure of such a project; but the main task still is the construction of IT systems.

- Because budgets are often tight, time investment in the methodology and language required for business-process modeling should not amount to more than 5-10% of the total project effort.

Practical Tips for Modeling Business Processes

Often one is warned about the complexity of business process analysis and business-process modeling. However, in our experience most business processes are thoroughly understandable and controllable. Rather, the lack of clarity and transparency makes them seem more complex than they really are.

In many cases, existing business processes are documented poorly or not at all. This can be traced to the fact that for many years most functionalities were treated as ‘islands’ instead of parts of comprehensive business processes. Because of that, the link between activities—the process chain—is missing. If this overview is missing, business processes seem complicated.

There are more hurdles to overcome if business processes are handled by IT systems. Most of the time, documentation of the manual workflow that is carried out between individual systems is not available. In other cases, the functionality of IT systems is unknown because processes run automatically, hidden somewhere in a black box, and only the input and output are visible.

Existing business process architectures or reference models that already exist can speed up and ease the modeling process. Comparing processes with similar or identical processes in other organizations can be helpful in identifying discrepancies and deriving possibilities for improvement.

Proper execution of Business Process Reengineering can be a game-changer to any business.

If properly handled, it can perform miracles on a failing or stagnating company, increasing the profits and driving growth.

Business process reengineering, however, is not the easiest concept to grasp. It involves enforcing change in an organization – tearing down something people are used to and creating something now.

And that’s not an easy task.

Jump to any section

- Business Process Reengineering Steps

- Step #1: Identity and Communicating the Need for Change

- Step #2: Put Together a Team of Experts

- Step #3: Find the Inefficient Processes and Define Key Performance Indicators (KPI)

- Business Process Reengineering Examples

So, What is Business Process Reengineering?

Business process reengineering is the act of recreating a core business process with the goal of improving product output, quality, or reducing costs.

Typically, it involves the analysis of company workflows, finding processes that are sub-par or inefficient, and figuring out ways to get rid of them or change them.

Business process reengineering became popular in the business world in the 1990s, inspired by an article called Reengineering Work: Don’t Automate, Obliterate which was published in the Harvard Business review by Michael Hammer.

His position was that too many businesses were using new technologies to automate fundamentally ineffective processes, as opposed to creating something different, something that is built on new technologies.

Think, using technology to “upgrade” a horse with lighter horseshoes which make them faster, as opposed to just building a car.

In the decades since, BPR has continued to be used by businesses as an alternative to business process management (automating or reusing existing processes), which has largely superseded it in popularity.

And with the pace of technological change faster than ever before, BPR is a lot more relevant than ever before.

Business Process Reengineering Steps

As we’ve mentioned before, business process reengineering is no easy task.

Unlike business process management or improvement, both of which focus on working with existing processes, BPR means changing the said processes fundamentally.

This can be extremely time-consuming, expensive and risky. Unless you manage to carry out each of the steps successfully, your attempts at change might fail.

Step #1: Identity and Communicating the Need for Change

If you’re a small startup, this can be a piece of cake. You realize that your product has a high user drop-off rate, send off a text to your co-founder, and suggest a direction to pivot.

For a corporation, however, it can be a lot harder. There will always be individuals who are happy with things as they are, both from the side of management and employees. The first might be afraid that it might be a sunk investment, the later for their job security.

So, you’ll need to convince them why making the change is essential for the company. If the company is not doing well, this shouldn’t be too hard.

In some cases, however, the issue is with the company not doing as well as it could be. Meaning, you should do your research. Which processes might not be working? Is your competition doing better than you in some regards? Worse?

Once you have all the information, you’ll need to come up with a very comprehensive plan, involving leaders from different departments. The management will have to play the role of salespeople: conveying the grand vision of change, showing how it’ll affect even the lowest-ranked employee positively.

Risk of Failure: Not Getting Buy-In From The Company

If you fail to do this, however, your business process reengineering efforts might be destined to fail long before they even start.

Business Process Re-Engineering can seriously impact on everyone in the company, and sometimes this can appear to be a negative change for some. Some employees might, for example, think you’ll let them all go if you find a better way to function (which is a real possibility).

In such cases, even if the management is on board, the initiative might fail because the employees aren’t engaged.

Usually, it’s possible to get the employees buy-in by motivating them or showing them different views they weren’t aware of. Sometimes, however, the lack of employee engagement might be because of a bad workplace culture – something that might need to be dealt with before starting any BPR initiatives.

Step #2: Put Together a Team of Experts

As with any other project, business process reengineering needs a team of highly skilled, motivated people who will carry out the needed steps.

In most cases, the team consists of:

- Senior Manager. When it comes to making a major change, you need the supervision of someone who can call the shots. If a BPR team doesn’t have someone from the senior management, they’ll have to get in touch with them for every minor change.

- Operational Manager. As a given, you’ll need someone who knows the ins-and-outs of the process – and that’s where the operational manager comes in. They’ve worked with the process(es) and can contribute with their vast knowledge.

- Reengineering Experts. Finally, you’ll need the right engineers. Reengineering processes might need expertise from a number of different fields, anything from IT to manufacturing. While it usually varies case by case, the right change might be anything – hardware, software, workflows, etc.

Risk of Failure: Not Putting The Right Team Together

There are a lot of different ways to mess this one up.

If the team consists of individuals with a similar viewpoint and agenda, for example, they might not be able to properly diagnose the problems/solutions.

Or, the team might involve too many or too few people. In the first case, the decision making might be slowed down due to conflicting viewpoints. In the later, there might not be enough experts in certain fields to create adequate solutions.

It’s hard to put all that down as a framework, as it depends on the project itself. There is one thing, however, that benefits every BPR team: having a team full of people who are enthusiastic (and yet unbiased), positive and passionate about making a difference.

Step #3: Find the Inefficient Processes and Define Key Performance Indicators (KPI)

Once you have the team ready and about to kick-off the initiative, you’ll need to define the right KPIs. You don’t want to adapt to a new process and THEN realize that you didn’t keep some expenses in mind – the idea of BPR is to optimize, not the other way around.

While KPIs usually vary depending on what process you’re optimizing, the following can be very typical:

- Manufacturing

- Cycle Time – The time spent from the beginning to the end of a process

- Changeover Time – Time needed to switch the line from making one product to the next

- Defect Rate – Percentage of products manufactured defective

- Inventory Turnover – How long it takes for the manufacturing line to turn inventory into products

- Planned VS Emergency Maintenance – The ratio of the times planned maintenance and emergency maintenance happen

- IT

- Mean Time to Repair – Average time needed to repair the system / software / app after an emergency

- Support Ticket Closure rate – Number of support tickets closed by the support team divided by the number opened

- Application Dev. – The time needed to fully develop a new application from scratch

- Cycle Time – The time needed to get the network back up after a security breach

Once you have the exact KPIs defined, you’ll need to go after the individual processes. The easiest way to do this is to do business process mapping. While it can be hard to analyze processes as a concept, it’s a lot easier if you have everything written down step by step.

This is where the operational manager comes in handy – they make it marginally easier to define and analyze the processes.

Usually, there are 2 ways to map out processes:

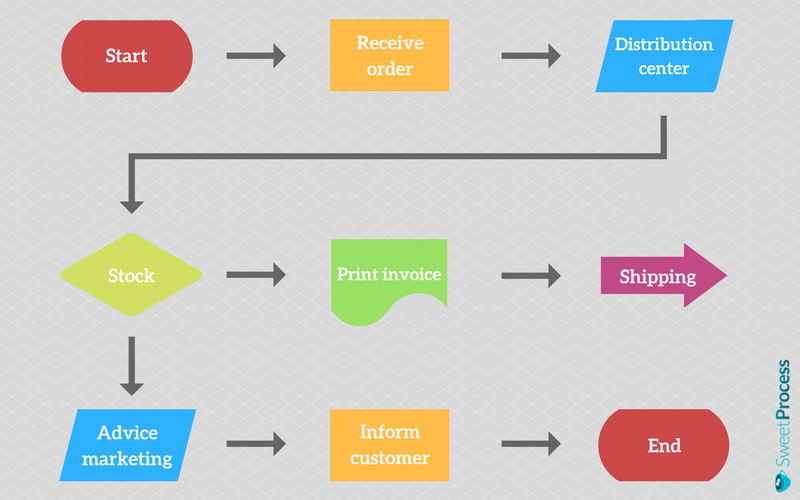

- Process Flowcharts– the most basic way to work with processes is through flowcharts. Grab a pen and paper and write down the processes step by step.

- Business Process Management Software – if you’re more tech-savvy, using software for process analysis can make everything a lot easier. You can use Tallyfy, for example, to digitize your processes, set deadlines, etc. Simply using such software might end up optimizing the said processes as it allows for easier collaboration between the employees.

Risk of Failure: Inability to Properly Analyze Processes

Or, to put it more succinctly – impatience. It’s uncommon for someone to try business process reengineering if they profits are soaring and the projections are looking great.

BPR is usually called for when things aren’t going all that well and businesses need drastic changes. So, it can be very tempting to hurry things up and skip through the analysis process and start carrying out the changes.

The thing is, though, the business needs analysis needs to be done properly, not rushed through to get to the more exciting parts.

There are always time and money pressures in the business world, and it’s the responsibility of the senior management to resist the temptation and make sure the proper procedure is carried out. Problem areas need to be identified, key goals need to be set and business objectives need to be defined and this takes time.

Ideally, each stage requires input from groups from around the business to ensure that a full picture is being formed, with feedback and ideas being taken into consideration from a diverse range of sources. The next step is to identify and prioritize the improvements that are needed and those areas and processes that need to be scrapped. Any business that doesn’t take this analysis seriously will be going into those next steps blind and will find that their BPR efforts will fail.

Any business that doesn’t take this analysis seriously will be going into those next steps blind and will find that their BPR efforts will fail.

Step #4: Reengineer the processes and Compare KPIs

Finally, once you’re done with all the analysis and planning, you can start implementing the solutions and changes on a small scale.

Once you get to this point, there’s not much to add – what you have to do now is keep putting your theories into practice and seeing how the KPIs hold up.

If the KPIs show that the new solution works better, you can start slowly scaling the solution, putting it into action within more and more company processes.

If not, you go back to the drawing board and start chalking up new potential solutions.

Business Process Reengineering Examples

The past decade has been very big on change. With new technology being developed at such a breakneck pace, a lot of companies started carrying out business process reengineering initiatives. There are a lot of both

There are a lot of both successful and catastrophic business process reengineering examples in history, one of the most famous being that of Ford.

BPR Examples: Ford Motors

One of the most referenced business process reengineering examples is the case of Ford, an automobile manufacturing company.

What Is A Business Process Improvement

In the 1980s, the American automobile industry was in a depression, and in an attempt to cut costs, Ford decided to scrutinize some of their departments in an attempt to find inefficient processes.

One of their findings was that the accounts payable department was not as efficient as it could be: their accounts payable division consisted of 500 people, as opposed to Mazda’s (their partner) 5.

While Mazda was a smaller company, Ford estimated that their department was still 5 times bigger than it should have been.

Accordingly, Ford management set themselves a quantifiable goal: to reduce the number of clerks working in accounts payable by a couple of hundred employees. Then, they launched a business process reengineering initiative to figure out why was the department so overstaffed.

They analyzed the current system, and found out that it worked as follows:

- When the purchasing department would write a purchase order, they sent a copy to accounts payable.

- Then, the material control would receive the goods, and send a copy of the related document to accounts payable.

- At the same time, the vendor would send a receipt for the goods to accounts payable.

What Is A Business Process Management System

Then, the clerk at the accounts payable department would have to match the three orders, and if they matched, he or she would issue the payment. This, of course, took a lot of manpower in the department.

So, as is the case with BPR, Ford completely recreated the process digitally.

- Purchasing issues an order and inputs it into an online database.

- Material control receives the goods and cross-references with the database to make sure it matches an order.

- If there’s a match, material control accepts the order on the computer.

New payable process

This way, the need for accounts payable clerks to match the orders was completely eliminated.

You can learn more about the case here.

Have any personal experiences with BPR? Was it successful? Why, or why not? Let us know down in the comments!